In my years at the writing center, I’ve often seen students approach the compare and contrast essay with a certain sense of dread. It can feel like a rigid, formulaic exercise in listing the obvious. But I want to encourage you to see it differently. Think of yourselves not as list-makers, but as curators. You are placing two ideas, two objects, or two figures side-by-side, not just to point out their features, but to reveal something new and meaningful about both.

The goal of this essay form is to make a nuanced argument born from careful observation. It’s one of the most fundamental acts of critical thinking—understanding something more deeply by seeing it in relation to another. So, let’s demystify the process and turn this seemingly tricky assignment into an intellectual adventure.

First, Finding a Meaningful Pair

Your professor may assign you a topic, but if the choice is yours, the task can be daunting. The secret is to avoid comparing apples and oranges, or worse, apples and asteroids. A strong comparison requires a shared context. You are looking for two subjects that are different enough to be interesting, but similar enough to have a genuine basis for comparison.

Instead of a random list, consider these conceptual pairings:

- Two historical figures from the same era: What do the innovations of Leonardo da Vinci and the political theories of Machiavelli reveal about the Renaissance mind?

- Two approaches to the same problem: How do the strategies of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s compare to the social media activism of today?

- Two artistic works from the same genre: How do two different horror films—one psychological, one visceral—manipulate the audience’s fears to achieve their effects?

The key is to move beyond a simple “Which is better?” and ask, “What does the comparison itself teach us?”

Structuring Your Argument: Two Paths

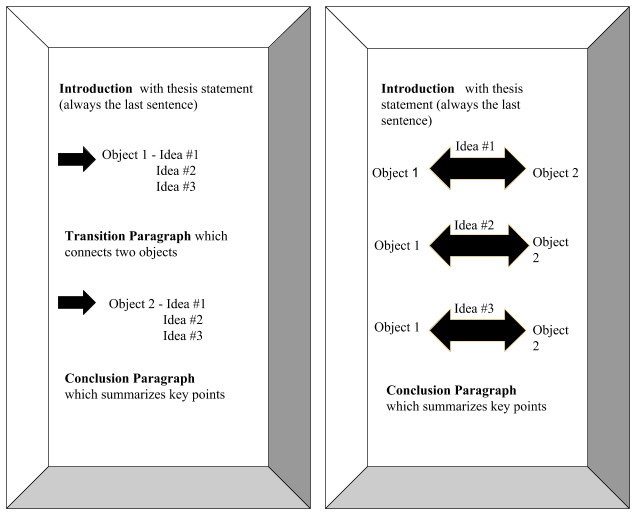

Once you have your pair, you need an architectural plan. There are two classic structures for this kind of essay. Neither is inherently better, but they serve different purposes.

- The Subject-by-Subject (or “Block”) Method: This is the most straightforward approach. You dedicate the first half of your essay to discussing all your points about Subject A. Then, you create a transitional bridge and discuss all your points about Subject B, making sure to relate them back to the points you made about A. It’s clean and allows for a deep dive into each subject. The risk? The essay can feel like two separate mini-essays rather than one integrated analysis. That bridge between the two sections must be exceptionally strong.

- The Point-by-Point Method: This structure is often more sophisticated and analytical. Instead of separating the subjects, you organize the essay around key points of comparison. For instance, if you were comparing two novels, your first body paragraph might compare the protagonists of both, the second might compare their central themes, and the third might compare their narrative styles. This method keeps the act of comparison front and center, constantly weaving the two subjects together. It forces a tighter, more integrated argument.

The Heart of the Matter: Your Thesis

A compare and contrast essay lives or dies by its thesis. A weak thesis simply states the obvious: “This essay will compare the similarities and differences between working from home and working in an office.” We already know you’ll do that.

A strong thesis makes an argument about the significance of those similarities and differences. It provides a roadmap for your reader. Consider this instead:

“While both remote work and traditional office life require discipline, the structured environment of an office inherently fosters opportunities for spontaneous mentorship and career growth, whereas the autonomy of working from home cultivates a deeper, more challenging form of self-reliance.”

Do you see the difference? This thesis presents a debatable claim. It tells the reader not just what you’re comparing, but what you’ve concluded from that comparison. Every paragraph that follows should now work to prove this specific argument.

Weaving it All Together: The Power of Transition

Transitions are the logical glue of your essay. In a point-by-point essay, they are crucial for moving between ideas. But they are most vital in a subject-by-subject essay, where you must guide your reader from one entire section to the next.

This can be a single, elegant sentence or a short paragraph that bridges your two subjects. For example:

Transitioning from remote work to office work: “While the remote worker’s world is defined by autonomy, the office environment operates on a different, though equally complex, set of principles centered on collaboration and shared space.”

And of course, arm yourself with the right language. Words are your tools for signaling your intent:

- To compare: Likewise, similarly, in the same vein, both share the quality of…

- To contrast: On the other hand, conversely, whereas, in contrast, despite this similarity…

Ultimately, the goal is not just to show that you can identify differences. It’s to construct a thoughtful argument that uses comparison as its primary evidence. It’s a skill that requires you to look closely, think critically, and build bridges between ideas—a skill that will serve you far beyond the classroom.