One of the key skills every student should have is saving money. You never know what kind of an emergency situation might happen. As soon as you begin a new stage in your life, you have to learn how to behave responsibly. Apart from the daily and monthly expenses, there is a student loan issue. That is why students try to stay within the budget and have a detailed plan. It is also one of the reasons why you might choose to struggle with the writing assignments on your own instead of hiring an expert to help you. The misconception of spending too much money on tutors does not let you enjoy the benefits of custom writing. It is a myth. Especially when it comes to writing short essays. Continue reading

Category Archives: Essay Writing

The Pecularities of Writing a Persuasive Essay – How to Write a Persuasive Essay

To persuade someone—to genuinely change their mind or inspire them to action—is perhaps the most powerful skill one can possess. It’s the engine of progress, the foundation of leadership, and the very heart of civic life. It is also, I have found, one of the most misunderstood pursuits in academic writing.

Many students believe a persuasive essay is about winning a fight, about bludgeoning the reader with facts until they submit. But this is a profound misconception. True persuasion is not a battle; it is an act of invitation. It is the art of guiding a reader, step by logical and emotional step, to a new perspective. It requires not a louder voice, but a more thoughtful and well-constructed case.

Let’s explore how you can build that case with integrity and grace.

Argument vs. Persuasion: A Crucial Distinction

First, let’s clear up a common point of confusion. You will often hear the terms “argumentative” and “persuasive” used interchangeably. While they are close cousins, they are not identical twins. Think of it this way:

- An argumentative essay makes its case primarily through logic and evidence (logos). Its goal is to convince the reader of a truth based on factual, rational support.

- A persuasive essay, while still built on a bedrock of strong argument, also strategically appeals to the reader’s emotions (pathos) and sense of ethics or character (ethos).

A good persuasive essay, then, doesn’t just prove a point; it makes the reader care about that point. It appeals to the head and the heart.

Laying the Groundwork: Before You Write a Word

The most persuasive essays are won long before the first paragraph is written. The groundwork is everything. Before you begin, take a moment to consider these two things:

- Your Position: What, precisely, are you advocating for? Your “ask” must be crystal clear. Are you trying to convince your reader to adopt a new viewpoint, to change their behavior, or to support a specific course of action? You cannot guide someone to a destination you haven’t clearly identified for yourself.

- Your Audience: This is the step most writers forget. Who are you trying to persuade? Imagine a skeptical but reasonable person. What do they currently believe about your topic? What are their potential objections or concerns? A masterful persuasive essay anticipates these counterarguments and addresses them respectfully within the body of the work. This shows you are a confident and fair-minded thinker.

The Architecture of Your Case

While you should never feel chained to a rigid formula, a classical structure provides a powerful and time-tested framework for building your case.

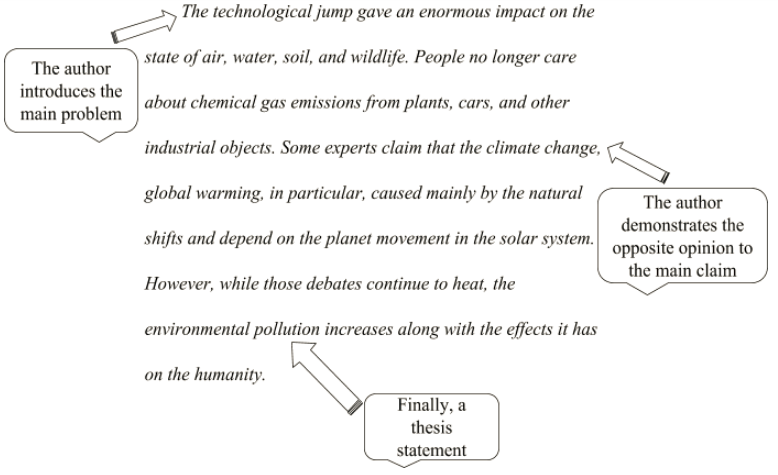

- The Introduction: This is your opening statement. It must do two things. First, it must engage your reader and establish the importance of the topic. Second, it must present your thesis statement—a clear, forceful declaration of the position you intend to champion.

- The Body Paragraphs: Think of these as the key pieces of evidence in your case. Each paragraph should present a single, distinct reason in support of your thesis. Begin with a clear topic sentence, and then support it with your evidence—this could be a statistic, an expert quotation, a historical example, or a logical deduction. This is also where you can subtly weave in appeals to emotion, perhaps through a brief, illustrative story that humanizes your point.

- The Conclusion: Your Closing Argument

I have seen countless students, weary from the work of writing, simply trail off at the end. This is a missed opportunity of the highest order. The conclusion is not a mere summary; it is your final, most powerful appeal to the reader. It’s where you tie all your points together with force and clarity.

A great conclusion should:

- Restate your thesis in a new, more compelling way.

- Briefly synthesize your main points, reminding the reader of the strength of your case.

- End with a memorable, impactful final thought—perhaps a call to action, a warning, or a hopeful vision for the future.

Consider this example, concluding an essay on the importance of local environmental efforts:

“Therefore, the responsibility for our planet’s health does not belong solely to governments and global summits. As we have seen, the most meaningful changes—from restoring local waterways to reducing urban waste—begin with the committed actions of individuals. By embracing practices like community recycling and supporting local conservation, we do more than clean our own backyards; we cast a vote for a sustainable future and reaffirm our power to preserve the Earth not as a distant concept, but as the home we cherish.”

This paragraph doesn’t introduce new information. It synthesizes, it elevates, and it calls the reader to see themselves as part of the solution. That, my friends, is the very essence of persuasion.